MU researchers developing method to quickly detect bacteria in food

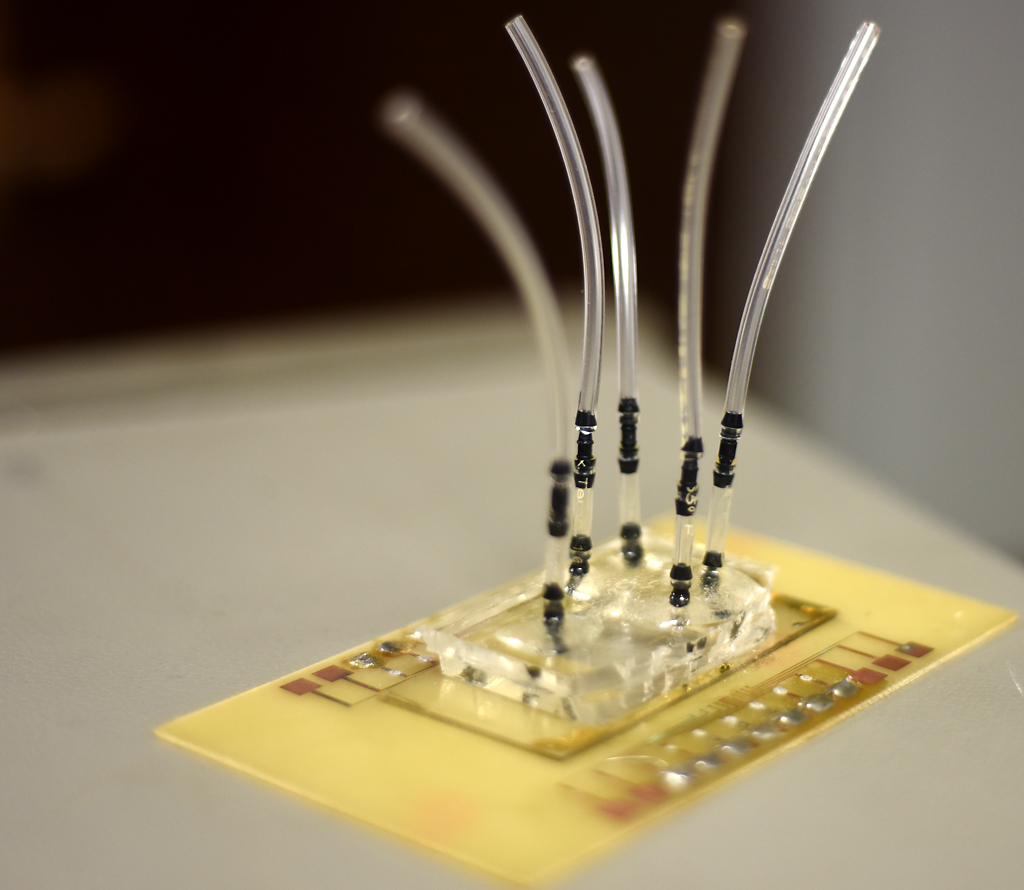

The biosensor that researchers Mahmoud Almasri(cq), Shuping Zhang, and Majed Dweik developed sits in a testing lab on Friday, September 13 in Columbia. Almasri says samples flow into three different sections of the sensor. If a section picks up an electrical signal, it means there is bacteria present in the sample.

CLAIRE HASSLER

Tests for the presence of dangerous bacteria like salmonella in raw and processed foods can take anywhere from one to five days to produce results.

Researchers from MU and Lincoln University are working on a tool that would cut that time to seven hours or less.

The biosensor for raw and ready-to-eat products uses a specific fluid that is mixed with the food to detect bacterial pathogens, which could be used along a food production line to allow producers to make sure their products are safe to sell. The device was tested on poultry products like turkey or chicken.

It was developed by three researchers, two of them from MU: Mahmoud Almasri, an associate professor of electrical engineering and computer science, and Shuping Zhang, a professor of veterinary medicine. The third researcher is Majed Dweik, an associate professor of physics at Lincoln University.

Detecting the bacteria before a food product hits the market can prevent foodborne illnesses. The CDC estimates that 48 million people per year are stricken with a foodborne illness. Of this 48 million, 128,000 are hospitalized and 3,000 die.

"This inspired us to design a highly sensitive device that can simultaneously detect multiple types of bad bacteria before products are being released to the public," Almasri said.

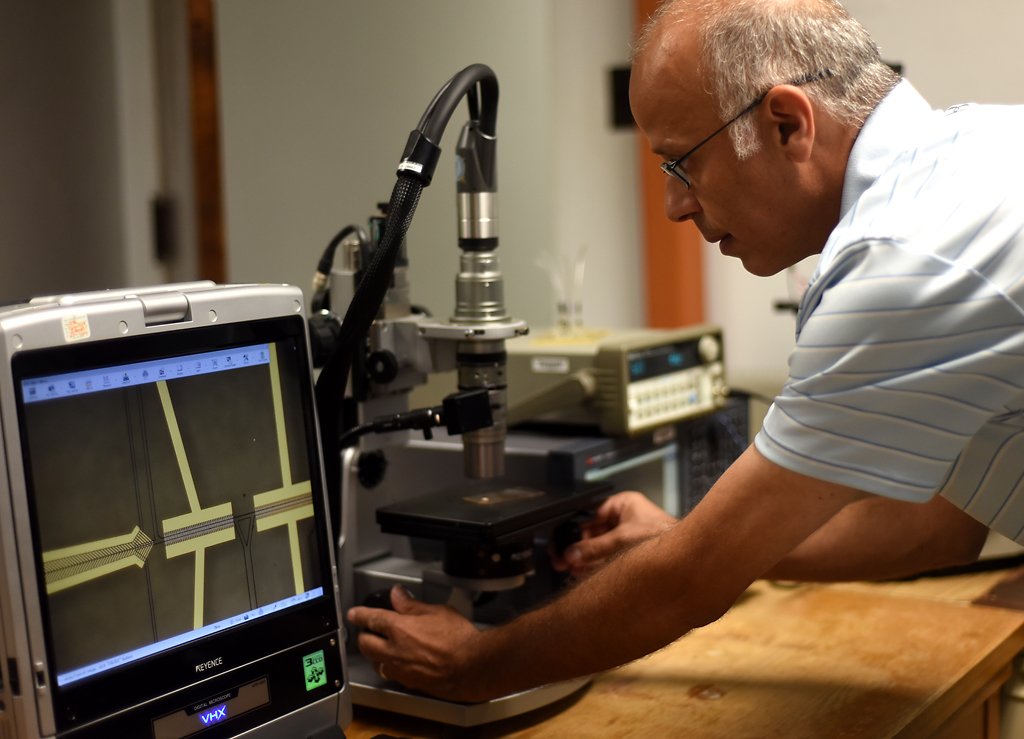

Mahmoud Almasri, an associate professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, demonstrates the route samples take through the biosensor on Friday, September 13, 2019 in Columbia. Almasri has been researching biosensing since 2009 and says he hopes this sensor will be commercialized in the next three to four years.

CLAIRE HASSLER

The sensor began as a way to detect potentially deadly E. coli in beef products. The project turned into a sensor that can detect multiple potentially harmful bacteria in poultry products with concentration as low as seven cells per milliliter in less than an hour without an enrichment culture.

The sensor can detect multiple different types of salmonella, along with listeria and campylobacter, Zhang said.

For the food industry, the device should help keep testing prices low and get products out to consumers much quicker, the researchers said.

The average cost of testing for a single pathogen is currently $25. Almasri's device is expected to cost between $4-8 per disposable chip and can test for three pathogens at once, according to the MU engineering website.

Almasri, Zhang and Dweik have published their findings in several journals, including Scientific Reports, PLoS One and Biosensors and Bioelectronics.

Zhenyu Chen, assistant research professor at the MU College of Veterinary Medicine, said the detection of foodborne pathogens using the biosensor requires no special instruments or laboratory and can be done in regular environmental conditions.

"Detection and analysis are also straightforward with no complex skills needed," he said via email.

The device is not yet available, but the researchers expect it to hit the market in three to four years.

Related coverage

Rainout shelters help Missouri farmers learn how to manage drought